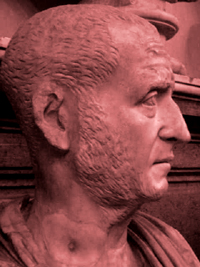

Antoninianus - IMP TRAJAN DECIUS

(RIC 11b)

- Rome Mint

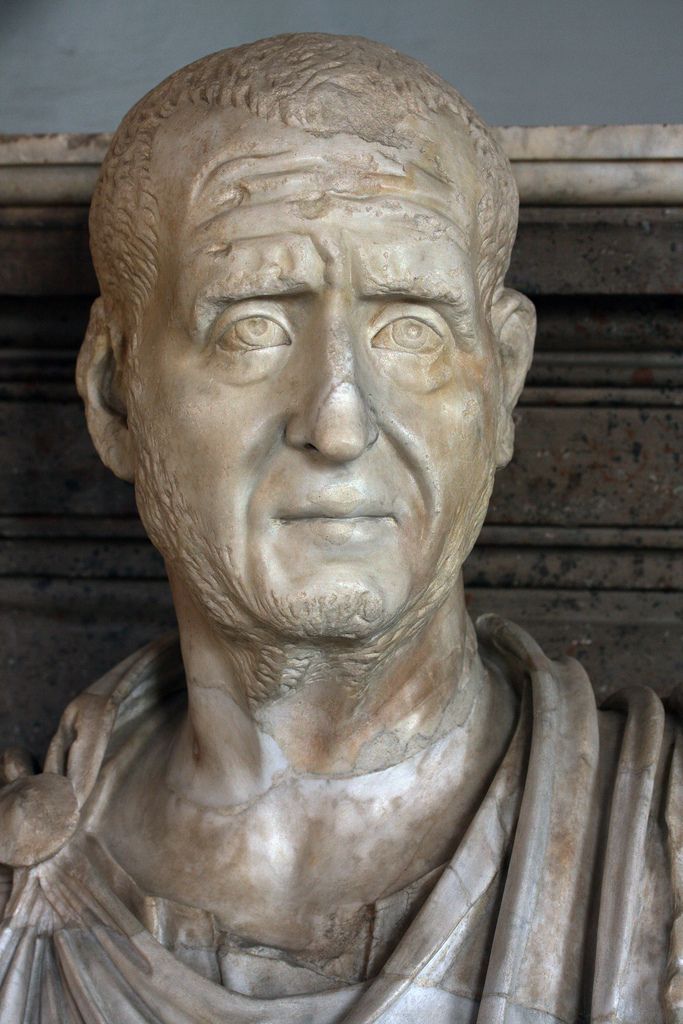

Gaius Messius Quintus Traianus Decius

Born: A.D. 201

Emperor: A.D. 249-251

Obverse: Portrait radiate, draped and cuirassed bust right - IMP C M Q TRAIANVS DECIVS AVG

Reverse: Decius on horseback with right hand raised in salute and holding scepter - ADVENTVS AVG

|

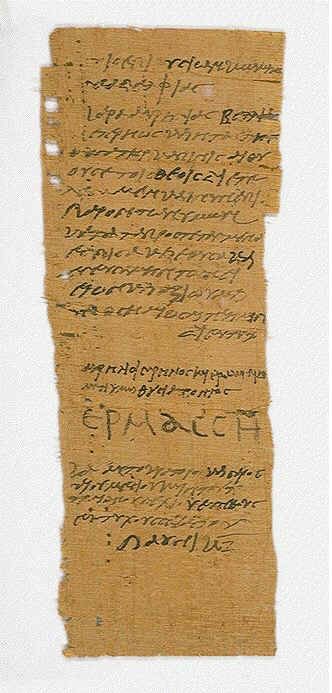

Inscriptions: IMP(erator) C(aesar) M(essius) Q(uintus) TRAIANVS DECIVS AVG(ustus) / ADVENTVS AVG(ustus) Emperor Caesar Messius Quintus Trajianus Decius Augustus / Arrival of Augustus (Commemorates the arrival of the emperor to Rome) Early Career and Ascension Decius is thought to have been born in Lower Pannonia, possibly in the town of Budalia near the city of Sirmium (modern Serbia). There is uncertainty as to the origins of his family as the name of his father is not known. He is the first in a line of emperors who would come from the province of Illyricum. He is characterized as having come from a provincial but aristocratic family of good standing, possibly with Italian origins. He served in a civil and/or military capacity in and around the Balkan provinces during the reign of Septimius Severus. Before being hailed as emperor, it is known that Decius had a long distinguished career as a senator serving as Consul sometime before 232. He also served as governor of Moesia around 232, Germania Inferior around 235 and later as governor of Hispania Tarraconensis around 237. Early in the reign of Philip I, his predecessor, it is thought that he held the important title of praefectus urbanus (Urban Prefect) of the city of Rome. Philip sent Decius to take up a command on the Danube. There he was set to the task of putting an end to the rebellion of the officer turned usurper Tiberius Claudius Marinus Pacatianus. He was also expected to stem the tide of Goths, Germans and Dacians who had flooded into the region. In 249 Decius marched on Pacatianus but upon his arrival, he found the usurper had already been killed by his men. Those men must have seen a suitable replacement in Decius as, shortly after his arrival, he was proclaimed emperor. Decius was very likely chosen by Philip for the experience he had with the people of this region, ironically this familiarity probably made Decius an ideal candidate for emperor to the local troops who were at least partly responsible for his accession. It is difficult to ascertain how keen Decius was to take up imperial responsibilities. Zosimus, a writer in Constantinople who lived hundreds of years later, reports that Decius was reluctant. Whether Decius sought imperial power or if it was thrust upon him against his will did not matter to Philip. He wasted little time leading his armies against Decius some time in June of 249. Philip was not terribly popular with either the troops or the senate at this time while Decius had loyal veteran troops and was certainly seen as a better candidate by the senate. Decius was certainly seen as a serious threat to Philip as evidenced by that emperors quick and personal response. The two clashed, possibly around Verona. Decius defeated Philip who lost his life either in battle, or at the hands of his own men. Zosimus states: "when the two armies engaged, although the one was superior in number, yet the other so excelled it in discipline and conduct, that a great number of Philip's partisans were slain and he himself amongst them" Philip's young son whom he had made his colleague was murdered by his guards in Rome upon hearing the news of his fathers death. With Philip dead and the blessings of the senate, Decius was now the emperor. Decius and the State Shortly after his acclamation by the senate Decius took the new honorific name of Trajan (Traianus). With this name he associated himself with a popular emperor. An emperor considered by many to be second only to Augustus from a time considered by many to be a golden age. The name was also fitting as Trajan, like Decius, had commanded troops on the Danube and along the German frontier. Most importantly the name was an attempt to endear him to the people as well as a statement of who he admired and who he would endeavor to emulate. Decius was an active emperor, mostly because he had to be. He seemed to have ambitious plans both short and long term. His aim seemed to be a restoration of traditional conservative Roman society and government. He served as consul every year of is reign and he looked to revive the office of Censor. He nominated the future emperor Valerian, the current princeps senatus (president of the Senate), for the position in 251. The holder of the powerful elected office of Censor, last held in the time of the republic, was traditionally responsible for taking the census, regulating public morals, piety, civic responsibility and administrating the state finance. He also embarked on the beginnings of a building program aimed at not only the restoration of older structures like the Coliseum (Trajan Amphitheater) which had suffered damage from fire, but also new building projects like the construction of the Decian Baths. According to Zosimus, Decius was: "a person of illustrious birth and rank, and moreover gifted, with every virtue" Aurelius Victor reports Decius was: "a man learned in all the arts and virtues, quiet and courteous at home, in arms most ready" Decius was and older man, close to 50, and conservative when he came to power. He was concerned with the lack of unity and loyalty within the empire and probably saw a return to traditional ways and civic duty as a cure. To this end, it is reported that he required all the inhabitants of the empire to make an offering to the traditional Gods of the state. These offerings were to be made in the presence of official witnesses who would then certify that the person had complied with the order by issuing a Libellus. This action was the beginning of what may have been one of the more damaging blows against the growing Christian faith, still in its infancy. Decius: Rome and the Christians In a world where Christianity is a major world religion and dominant in the west, Decius is largely remembered for having persecuted Christians. The edict does not survive so it is unknown in what form it took nor is there any stated reason for issuing it. While the wording of the edict and the reasons for requiring this show of faith and loyalty are not known, the edict was probably not directed at Christians alone as it seems all the people of the empire were expected to comply without regard to their religion. Most pagan sources are kind to Decius characterizing him as being "filled with all skills and virtues" and "calm and congenial in civil affairs." In Christian history he was generally characterized as wicked, an emperor who hated Christianity. They appear quite sure that Christianity was the intended target of the decree and his aim for issuing it was to eliminate those who follow that religion. Most of the literary sources for Decius are questionable at best and Christian sources generally depict him as a two dimensional villain for stories about martyrs. Historically speaking there is little to support, or dispute, this claim as his motives for the decree and in what form it took exactly remains unknown. In general there is scant information about Decius, his origins, his life, or his reign. From the few literary reference, coins and inscriptions available to us, Decius is seen as a conservative and an adherent to traditionalist Roman ways. If this is true then these qualities would certainly put him, in some measure, in opposition to Christians. At this time Christians generally stood opposed to anything pagan and placed the laws of their god and savior above all else, including the Roman state. The Roman state may have seen them as standing opposed, or lacking loyalty to the Roman state and its laws. In many ways they were right. From its inception Christianity existed within the Roman Empire. Rome and Romans would play a major role in Christian history from day one. In general Christianity had difficulty coexisting along side, and within, the Roman state so there have certainly been times when the two overtly clashed. There is simply not enough evidence to say what the motives of the state were concerning this decree let alone if they were even aware of what a profound effect it would have on Christians. They may very well have still, at this time, existed mostly under the radar of high ranking pagan officials. The few non-Christian sources which discuss Decius are brief and seem to view him in a favorable light. Decius was deified after his death which may attest to his popularity at the time with pagans who were still the great majority. These sources do not mention a Christian persecution or this decree. Only Christian sources such as Eusebius, a writer born more than a decade after the death of Decius and who wrote during the persecutions of Diocletian, or Lactantius, who also wrote many years later and saw Decius as a base villain and portray him as actively anti-Christian, mention this decree or the persecution which followed. The edict, in whatever form it may have taken, is generally accepted to have been issued as examples of Libelli have been found (left). These are slips of papyrus from the time of the reign of Decius that record individuals who have given offerings at an alter before witnesses who then confirm they have done so. Even though this edict was apparently not overtly directed at Christians alone, in the end it was the Christians who were most affected by it. Traditionally, Pagan Romans (an indeed most pagan religions) were remarkably open minded towards other religions. Many Romans not only worshiped their own gods but they often incorporated the gods of others into their worship as well. Eventually enough Romans would even adopt Christianity to the point that it became not only the dominant religion but the only legal religion within the empire. Many different religions and Gods were worshiped within Rome and many Romans and pagans saw other gods from other cultures as worthy of respect as much, if not more in some cases, as their own Gods. They would often adopt these other gods and worship them as well thus they did not understand why a Christian or a Jew could not do the same. Pagan Romans seldom instituted any policy which banned the worship of other religions within its borders. Any such laws were, more often than not, reactions to specific religions whose very nature conflicted with the Roman state, its pietas and its laws. An example of a religion specifically banned by Rome would be the Druids. They were thought to have practiced human sacrifice, something which was abhorrent to the Romans. When Christianity first arrived and Romans began to hear the story of Jesus and how they worship in their underground ceremonies and how they lived their lives in anticipation of their death, they were shocked. This seemed more like a death cult or witchcraft than a proper religion. They heard about people working 'miracles', raising the dead, healing the sick, walking on water, this all seemed like sorcery or superstitio. It is clear many early Romans had an aversion towards a religion which tells its worshipers to drink blood and eat flesh. Even when they are made aware the Eucharist is just a re-enactment using bread and wine as an effigy of the body and blood of their savior, it still remained distasteful to many. Christians of this time often chose to stand apart. While they no longer worshiped in secret under ground, the very nature of Christianity, as many saw it in these times, required them to live outside mainstream society of the time. Often their beliefs and their tenuous adherence to these beliefs, even when it is at the cost of their very lives and the lives of loved ones, meant that they often defied laws and decrees and clashed with the state. Defiance of the laws meant many suffered the fate of criminals for it and became martyrs, champions of Christ who lost their lives in uncompromising service to the lord assured of their place in paradise. The men were seen by Romans as yearning for death. Over the years the Christian population grew and infiltrated all classes, nationalities and races scattered throughout the empire. They were far from being the masters of Europe they would soon become but they were no longer the small mysterious underground Jewish apocalyptic death cult of the past. Early Christians saw no higher authority than their god and savior and no law higher than the laws and the tenets of their faith, this included the laws of the Roman Empire if they happen to run contrary to Christian doctrine. Because they often placed their God and that Gods laws above that of the Roman state, the relationship between the state and Christians would often be contentious. The only way Christians seemed to be capable of complying fully with laws of the state at this time would be to live in a state whose laws were tailored towards the Christian doctrine. If Decius indeed saw the Christian faith as a danger to the traditional Roman state, he was quite perceptive as Christianity would indeed eventually command the Roman state, outlaw paganism, and become the dominant, if not the exclusive, religion of the western world. Decius would have been at least familiar with Christians although it is impossible to know the extent of his knowledge of their beliefs. Regardless of his motives, the edict represented a test of faith for the Christian population and the results of that test is generally recognized to have had profoundly negative affects on the already somewhat fractured nature of the Christian community at this time. Christians valued and still value Christian martyrdom. People who gave their lives, often in the most brutal ways, for their religion. Early Christians were non-violent to the point they would not take arms against an enemy or defend themselves, many would not even flee if given a chance. They would stay and submit to any punishments as a show of the ultimate loyalty to their god. For this they would be revered by the church and assured a place in heaven. To Pagans it may have seemed like they welcomed death. Their savior was brutally executed at the hands of the Romans and certainly many followers saw an emulation of this death as the greatest act of faith. Pagans often saw Christians as a death cult as they lived their lives only in preparation for the afterlife. To many they also seemed like a doomsday cult as they often predicted and even seemed to desire the end of times. This is possibly how Decius would have seen Christians. It is not known exactly how many Christians were either imprisoned, enslaved, banished, fled, or executed as a result of this edict. It seems most likely that this edict was enforced with variable degrees of severity depending on the location as was common in a large and widespread empire. Also, with economic crisis and looming external threats, it is likely that Decius had far greater concerns to occupy him than making sure his edict was being faithfully implemented across the whole of the empire. Certainly there were those administrators who probably zealously implemented the decree, while others may have been less eager. Although Christian leaders made clear that the duty of the Christian was not to fight, not to run, and not to comply, still many Christians chose to comply, others paid corrupt officials to buy their Libelli, still others fled persecution including high ranking Church officials like the Bishop Cyprian of Carthage. Apparently the Bishop was too important to suffer punishment for disobedience with his flock. Although he fled choosing his own safety over his flock, it was reported that he harshly condemned those who stayed and complied or bribed officials to preserve their freedom and possibly their lives. How many stayed and openly refused to comply is unclear but it seems that in some cases the punishments for noncompliance could be harsh. Fabianius, the Bishop of Rome, clearly illustrated what he thought was the Christians duty at such a time. He refused to comply and was one of the earliest victims. He was put to death becoming the most prominent Christian to be martyred in opposition to the Edict. Still there is little evidence to suggest open season on Christians or any form of whole sale slaughter under Decius. This persecution may have even been an accidental side affect of a decree issued for an entirely different reason. This may not have even registered on the pagan imperial radar as non-Christian sources do not even mention the decree itself or the effect it had on Christians. The true damage to Christianity caused by this decree was in the further division it created in a church already lacking in unity. Many of those who defied the order without fleeing or bribery would condemn those who complied, fled, or resorted to bribery. Those who defied the edict and were imprisoned, enslaved or were executed became martyrs. There was then the matter of what to do about those who complied or resorted to bribery but wished to still be Christians. There were those who advocated forgiveness and there were others who saw these people as apostates. These people favored anathema for those people who abandoned their duties to Christ and the Church when truly tested. Christians would, of course, eventually settle these issues. A Christian state would in time take the place of the pagan Roman state and, ironically, in their own quest to eliminate all other religions they would kill, banish, torture, force conversion and burn or demolish pagan temples. This empire and its successor states would rigorously and overtly persecute all other religions within the borders of their Christian nations.

Family, War Against the Goths, and Death With his wife Herennia Cupressenia Etruscilla he had two sons, Herennius and Hostilianus. Herennius was the eldest son, most likely an adult as he accompanied his father and participated in his campaigns. Hostilianus was probably still quite young during his fathers reign. He did not accompany his father on campaign and appears as a young boy on much of his coinage. Both were made Caesars by their father although Herennius would shortly after be risen to Augustus. There were several attempts at usurpation and numerous pressing external threats to the empire. Iotapianus had rebelled in the east under Philip and had yet to be dealt with upon that emperors death. His rebellion was rooted in opposition to new taxes raised by C. Iulius Priscus, brother of Philip. Because this was more a civil revolt than a military backed usurpation, this rebellion did not seem to be a major threat. It appears likely the rebellion lost steam with little if any need for military force and Iotapianus is said to have been killed by his own men shortly after Decius took power. His head is said to have been delivered to Decius while in Rome in 249. Decius and Herennius campaigned every year of his reign against threats all across the Danube. Father and son were increasingly away from Rome campaigning against various Germanic tribes like the Carpi and Gepidae as well as Goth forces under the leadership of King Cniva. These forces were raiding deep into Roman provincial territory particularly in Moesia, Dacia, Thrace and Pannonia. Julius Valens Licinianus, a senatorial aristocrat, took advantage of the emperors absence to make a grab for power in Rome. Although he appears to have had some popular support for this action, his bid for power ended with his execution after just a few days. While the tribes beyond the Danube had made it a habit of crossing to raid Roman territory, in 250 and 251 they crossed in far greater numbers. This may have been due in part to a refusal by Philip to make payments promised by Maximinus in exchange for peace. It may also have also been apparent to the tribes along the Danube that Rome was finding it increasingly difficult to adequately defend against the numerous threats along this border. Decius and his son probably spent much of their time and efforts in 250 and 251 campaigning against these increasingly frequent incursions. Decius successfully defended Dacia from incursions by the Carpi. This required him to leave the province of Moesia Inferior relatively unguarded. The Goth general took this opportunity to march his sizable army of allied tribes into the province. His troops may have lay siege unsuccessfully at Marcianopolis and at Novae where he may have been repelled by the future emperor Gallus who was the provincial governor at this time. Decius pursued the army of Cniva and the two may have clashed several times with the armies of Decius winning a minor victory at Nicopolis ad Istrum. We know he was, at least, promoting a successful campaign and victory over the Goths as some of his coins bare the reverse inscription Victoria Germanica as well as an inscription which styles Decius as Restitutor Daciarum. Cniva retreated after his defeats at Nicopolis but doubled back and marched on Philippopolis with Decius in pursuit. Cniva turned and caught Decius by surprise near the town of Beroe (named by the Romans Ulpia Augusta Traiana, modern day Stara Zagora) forcing Decius to retreat and regroup. Jordanes states: "While he (Decius) was resting his horses and his weary army in that place, all at once Cniva and his Goths fell upon him like a thunderbolt. He cut the Roman army to pieces and drove the Emperor, with a few who had succeeded in escaping, across the Alps again to Euscia in Moesia, where Gallus was then stationed with a large force of soldiers as guardian of the frontier. Collecting an army from this region as well as from Oescus, he prepared for the conflict of the coming war." This allowed Cniva time to reach Philippopolis. The Goth king besieged the city and captured it 250 AD, probably with the help of Titus Julius Priscus, the governor of Thrace who was then declared emperor. Once news of his acclamation as emperor reached Rome he was declared an enemy of the state and was killed soon after the death of Decius, possibly by the Goths who he is reported to have aided in taking the city. King Cniva probably had time to loot the city and the territory before setting off toward home with his captives and spoils.

While sources vary in their retelling of the details concerning the events that followed, all agree that Decius engaged Cniva near the Moesian city of Abrittus. Cniva seemed to have occupied an advantageous position in familiar terrain while Decius is reported to have been cut off and forced to fight in marshy terrain. All sources agree that Decius died in this battle though they disagree in what manner he died. Jordanes and Aurelius Victor report Herennius had been struck by an arrow, possibly in a skirmish before the battle, and the death of his son may have driven Decius to rush into a conflict with the retreating barbarian army. Jordanes states: "In the battle that followed they quickly pierced the son of Decius with an arrow and cruelly slew him. The father saw this, and although he is said to have exclaimed, to cheer the hearts of his soldiers: 'Let no one mourn; the death of one soldier is not a great loss to the republic', he was yet unable to endure it, because of his love for his son. So he rode against the foe, demanding either death or vengeance, and when he came to Abrittus, a city of Moesia, he was himself cut off by the Goths and slain, thus making an end of his dominion and of his life. This place is to-day called the Altar of Decius" Zosimus claims he fell due to treachery on the part of Gallus: "Gallus, who was disposed to innovation, sent agents to the Barbarians, requesting their concurrence in a conspiracy against Decius. To this they gave a willing assent, and Gallus retained his post on the bank of the Tanais, but the Barbarians divided themselves into three battalions, the first of which posted itself behind a marsh. Decius having destroyed a considerable number of the first battalion, the second advanced, which he likewise defeated, and discovered part of the third, which lay near the marsh. Gallus sent intelligence to him, that he might march against them across the fen. Proceeding therefore incautiously in an unknown place, he and his army became entangled in the mire, and under that disadvantage were so assailed by the missiles of the Barbarians, that not one of them escaped with life. Thus ended the life of the excellent emperor Decius." Zonaras states: "he and his son and a large number of Romans fell into the marshland; all of them perished there, none of their bodies to be found, as they were covered by the mud." Aurelius Victor states: "On foreign soil, among disordered troops, he was drowned in the waters of a swamp, so that his corpse could not be found. His son, in fact, was killed in the war." The Christian writer Lactantius depicts his death in significantly more hostile and brutal detail: "he was suddenly surrounded by the barbarians, and slain, together with great part of his army; nor could he be honored with the rites of sepulture, but, stripped and naked, he lay to be devoured by wild beasts and birds, a fit end for the enemy of God." Aurelius Victor says Decius ruled for just thirty months although it seems more likely that he ruled closer to two years from around June of 249 to about June of 251. He was the first emperor to meet his death in the field against a foreign foe. At his death, Decius was purportedly fifty years of age. He likely died on or before June 24, 251 as the Decii are listed as Divi (Divine) on an inscription with this date on it. Eusebius claims both Decius and Herennius were deified after death. Many contemporaries seem to see Decius as a good emperor and the circumstances of his death heroic. The fact that he was the first emperor to fall to a foreign enemy alone would certainly be seen as tragic. Mostly non-Christian chroniclers depict him in a favorable light. Zosimus says he was "gifted, with every virtue" while Aurelius Victor claims Decius was "a man learned in all the arts and virtues, quiet and courteous". Christians saw his death as a fitting end to a wicked man. Christian writers unanimously condemn him. Lactantius sums up the character of Decius as "an accursed wild beast, to afflict the Church. It seems as if he had been raised to sovereign eminence, at once to rage against God, and at once to fall." Eusebius regularly describes him as "wicked". The truth likely lay somewhere closer to the former than the later as it is almost certain that his motive was not the destruction of Christianity. As is common for an emperor of this time and one who reigned so briefly, much of the information that comes to us comes from mostly biased second hand sources. They are reporting what it is they have read and heard and in some cases they are adding their on assessments and judgments. As historians down the ages attempt to extrapolate a clear image of Decius as an emperor and a man, that image becomes more blurry, or in the case of church history, the image becomes more sharply black and white. The most apparent truths regarding this emperor and his short time in the spotlight of history would be that he was probably a proponent of traditional conservative Roman institutions, customs, and pietas. He was an aging but experienced Roman aristocratic statesman with what seemed to be a clear long term vision of a return to the greatness of the old Roman state and its Gods. This vision put him in conflict with early Christians who chafed under Roman rule on good days. In the end he was a man who probably spent his life in the service of the Roman state who vigorously defended the empire at the cost of his life. Trebonianus Gallus was named emperor by survivors of the Battle of Abrittus and the senate soon confirmed their choice. Reports of treachery by Gallus are often looked upon with suspicion as it seems unlikely that troops would raise a man who was suspected to be complicit with the death of so many of their fellow soldiers. Gallus would also adopt Hostilianus as a colleague but the young emperor would die of natural causes soon after, a victim of the Cyprian Plague. |